An excerpt from Cheryl Angelina Koehler’s excellent article on Frog Hollow’s compost program in this month’s Edible East Bay – Composting to Save the Planet. To read more please see their print magazine or edibleeastbay.com

The real dirt on Farmer Al Courchesne of Frog Hollow Farm is some very rich humus indeed. Compost. Huge heaps of it.

“We see this as a model for farming that could address climate change,” says Courchesne, whose conversion to the way of composting grew in earnest about four years ago on account of some pastries.

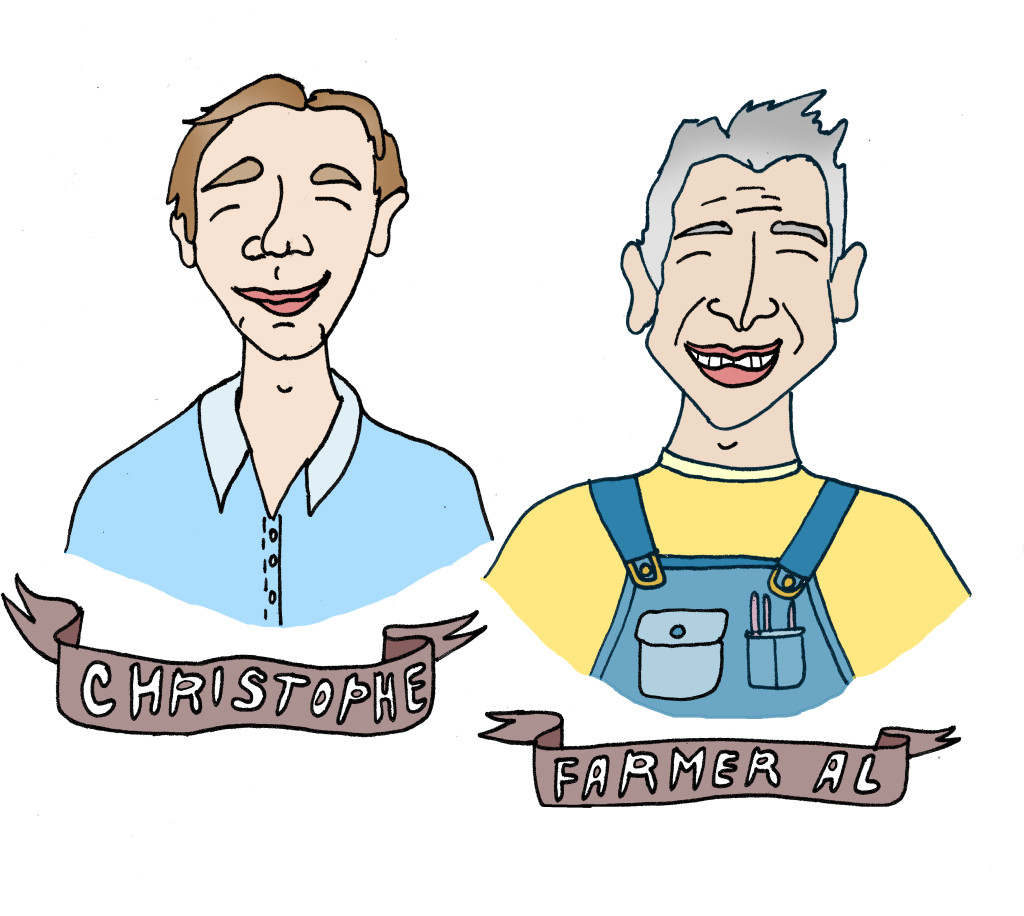

Pastries? Well, yes. Al loves them, and who doesn’t. But this farmer, known for his big smile, good appetite, and blue overalls, also is keen on sustainability systems, and close to a decade ago when he set up a bakery on his 143-acre Brentwood fruit farm, pastries certainly were on his mind. Preserving, as well as creating value-added baked fruit items to sell, meant he could offer more year-round work to his farm staff, and it also would put some of the less- pretty pieces of his orchard’s fruit to delicious use.

But the pastries did something Farmer Al hadn’t exactly expected: They enticed two special customers into the Frog Hollow Farm to Table Café at the San Francisco Ferry Building Marketplace. Christophe Kreis and his wife Monique La Fleur, both molecular biologists, had made it a habit to stop at Al’s café for a pastry each Saturday when they came to shop at the Ferry Plaza Farmers’ Market.

One of those mornings Kreis, who is a certified Master Gardener, got on the topic of compost with Farmer Al and both found they were acquainted with and mutual admirers of Elaine Ingham, a soil microbiologist and founder of Soil Foodweb Inc., who is currently promoting the virtues of composting through her role as chief scientist at the Rodale Insti- tute, that venerable American think tank of organic gardening.

Kreis, as it turned out, was actively looking for a way to transition out of his HIV research position at UCSF into environmental work. As someone with the background to understand the intricacies of soil biology, he was, as he put it, “fascinated by compost.” The result of the conversation was that Kreis allowed himself to be lured out to the other side of Mt. Diablo where he now reigns as Courchesne’s “Master Composter” at Frog Hollow Farm.

Since then, the two men have gotten themselves in knee-deep with Mother Nature, helping her out with that intricate sustainability system she designed for keeping carbon in balance on the planet. Although it looks like dirt, compost is one of nature’s great wonders: It forms the very heart of a grand web of beneficial relationships between the ground, the atmosphere, all creatures great and small (from microbes to ruminants), and healthy plants—like fruit trees.

Thermophilic composting, aka hot composting, can only be carried out effectively within a large operation, such as a farm or a green-waste recycling system like the ones that process the yard trimmings and kitchen scraps we city folk throw in our curbside green barrels. And while both types of venture can keep large quantities of green waste from being dumped in piles or landfills—where it rots anaerobically, producing large quantities of greenhouse gasses—the advantage of on-farm composting is that the fertile end product can be used right there on site. No trucking involved. According to Courchesne, few farms, even forward-thinking organic farms, are doing much large-sale composting.

“Garbage and waste are not in our lexicon,” says Farmer Al, who prefers the word “residue” for all the tree trimmings, untenable fruit, food scraps, and shredded cardboard fruit boxes the Frog Hollow Farm trifecta of workspaces—orchard, café, and kitchen—produces. Nearly every bit of residue gets recycled into the compost. The addition of regular loads of horse-soiled hay from a couple of neighborhood horse barns provides essential nitrogen and precious micronutrients that contribute to the conversion of the residues into compost as well as toward that humus’s richness. At the tidy vermicomposting compound near the Courchesne family home, the café’s coffee grounds are put to use (along with other valuable organic matter) to support a teeming wriggle of worms. Vermicompost, which is compost that is essentially digested by earthworms, is especially useful for fertilizing vegetable gardens like the one FHF tends in order to grow their own greens for the café’s salads, soups, and sandwiches.

The blossoms will be on the stone fruit trees right about the time this article reaches the public, and that would be a grand time to head out through the FHF orchards to Kreis and Courchesne’s thermophilic composting site. There, a visitor would find six or more long piles (called windrows) of compost-in-progress. Each windrow sits steaming for three months as microbes break down the materials, and during that time gets run through on five or six distinct occasions by a dedicated piece of equipment called a windrow turner: The turning of the materials discourages methane production that would occur inside an untended heap or landfill. It also helps achieve an even 130 degrees throughout the pile. That’s temperature at which most weed seeds and pathogens will die, leaving behind a lovely teaming mass of beneficial protozoans, fungi, bacteria, nematodes, and arthropods. These small creatures are all esteemed residents of the dark, rich, organic material known as humus, and each plays its unique role in the complex interrelationships between healthy plants and healthy soils. Courchesne estimates his operation produces about 4,000 pounds of humus from compost per year, all of which is used to fertilize those lovely fruit trees, which in turn produce fruit that Courchesne swears tastes measurably better than similar fruit produced by conventional farming practices.

Courchesne has been running a certified organic operation for most of the 39 years he’s been on his land. To be certified organic, a farm has to eschew the use of synthetic pesticides, fungicides, and petroleum-based fertilizers, which increasingly are being implicated in environmental degradation and a large carbon footprint for industrial farming. Farmer Al had been purchasing organic fertilizer and practicing integrated pest management in lieu of the chemicals, but as he began learning about compost, he found himself rethinking the whole equation of his organic farming business.

Off the top of his head, this farmer estimates that he was trucking in an estimated $125,000-worth of organic fertilizer per year to feed the fruit trees. Reconsidering that figure as an annual budget that could instead fund production of his own fertilizer through composting, he made the leap and purchased the following equipment:

Dump truck $15,000

Wood chipper $30,000

Cardboard shredder $15,000

Compost turner $25,000

Compost spreader $25,000

Those are rough estimates, but that total of around $110,000 penciled out pretty elegantly to make the farm-produced compost fertilizer a viable choice from year one. Courchesne realized there would be additional costs each year to man and maintain the program, but much of that money goes right into his own workers’ pockets—a value this farmer holds dear.

Looking at the value for Mother Nature and the farm, here’s a partial list of the benefits Farmer Al sees that come with composting:

Better water-holding capacity and retention in the soil

Higher soil aeration (which allows better root structure)

Enhanced ability of plants to absorb minerals

Storing of carbon in the soil

Restored balance of the farm ecosystem, thereby suppressing disease pressures

Strengthened plant resistance to insect attack

Stimulated plant vigor and growth

Number 7 is especially significant toward mankind’s hope for saving the planet (or rather its residents) from the effects of climate change. As we all learned in school, healthy plants, through photosynthesis, absorb CO₂ out of the atmosphere and sequester it back into the soil. More and healthier plants means more carbon sequestration and also that there’s more good food being produced. Farmer Al is betting on composting to bring the amount of atmospheric CO₂ his farming operation emits into the negative zone. He might not save the planet, but he’s setting a great example.

And there’s a simpler equation worth noting: Less atmospheric CO₂ means more delicious fruit for making tarts, galettes, turnovers, ice cream, sorbet, jam, curds, cookies …

Follow

Follow